Most of Friday was spent traveling from Ngorongoro crater in Tanzania to Petra in Jordan. The journey took us around and down the Crater rim, back to our local airport, and from there to the Kilimanjaro airport. Departing, I took this shot of Mount Kilimanjaro.

It was a 4 ½ hour flight northward across central Africa, over the Sudan, and then up the Gulf of Aqaba into Aqaba, Jordan (that is the Sinai on your left).

During the flight, I lectured on “Petra and Nabataean Civilization.” (The next day, I was pleased to see what I said confirmed by our actual visit to Petra.) After landing, a two-hour bus trip north brought us to Wadi Musa, the village adjacent to Petra, itself a UNESCO world heritage site.

On Saturday morning we were up and out early for the short walk from our hotel to Petra’s entrance. Passing the “Djinn Blocks” (possibly an-iconic representations of one or another of the Nabataean gods) . .

. . . .we met some guards wearing cheesy plastic helmets who were said to represent the “original guards of the site,”

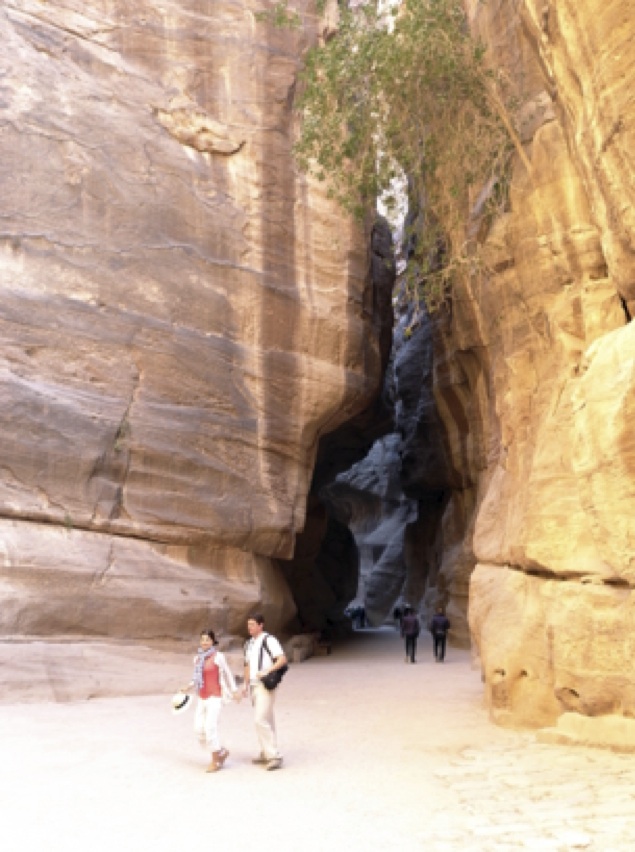

(this can be dispensed with) and entered the Siq. This three-quarter mile long cleft in the mountain is a tunnel in stone that protected Petra and made it a secure site for the construction of royal and other tombs by the Nabataeans.

In addition to a long water-channel running the length of the Siq, we also encountered niches and bas-reliefs devoted to the gods on the walls, notably this one dedicated to Dushara, the high mountain god associated with the Nabataean royal lineage. Dushara, at the head of the Nabataean pantheon, is usually represented an-iconically, as in the simple block in this sculpture:

Halfway through the Siq are the remains of a bas-relief of a camel with its minders. The meaning of this carving is unclear. Is it a representation of the merchants and their beasts whose trade in myrrh and frankincense made the Nabataeans (312 b.c.e. to 363 c.e.) wealthy? Or is it one of the animals brought for sacrifice to Dushara at the high place altars above the city? My lecture had touched on these questions, but the answers remain unclear.

Suddenly on rounding a bend, the Siq came to an end, and there before us was the beautiful “Treasury” (Khazneh). This misnamed site is one of the impressive rock-carved tombs for which Petra is famous. This photo only hints at the complexity of its many adornments.

Look for example, at the many small blocks that ring the cupola:

Just past the treasury, as we walked toward the vast open area that is Petra’s city center, is the theater, with its 45 rows of seats that could accommodate 6,000 people (the niches above are rock tombs whose completion was interrupted by the building of the theater).

Back over my shoulder was a magnificent collection of rock-cut tombs on the mountain wall above.

And ahead, moving westward, lay the colonnaded main street with its three sites: the Great Temple to the left, the barely visible Temple of the Winged Lion on the hill at the right (a semi-an-iconic representation of Dushara’s consort, al-Uzza or Allat, was found here), and straight ahead, the imposing walls of the Qasr al-Bint, misnamed as the Temple of the Pharaoh’s daughter (a result of a late and faulty legend), but actually the chief temple of the city and dedicated to Dushara.

At this point, one of the guides volunteered to lead us to the Qasr al-Bint by a round-about path on hills to the left of the picture above. I followed, a nearly fatal decision.

At one point, as we neared the Qasr, the pathway became a narrow ledge. The path ahead of the people at the center was no more than 6 feet wide, and to their left was a 200 foot drop down a rocky gorge (which you can see as lighter colored rocks beyond the gray boulders). As I reached where they are, I slipped on a pebble, and fell toward the edge. I would like to say that my entire life flashed before me, but all I could first think about was possible damage to the camera hanging from my neck. In an instant, however, I realized I was a foot or two from tumbling over the edge.

Fortunately, I slid no further, and with help and only minor bruises and cuts, I picked myself up. From that point on, I continued along the path, clinging to the rock wall to my right. Ahead of me on the narrow path was a traveler shaking in fear who had to be nudged around the bend, and further on, another traveler who slipped and fell as I did. In all a terrifying experience, the surviving of which made my day. Being alive never felt so good. In the future, I hope our guides are warned that this side excursion may be too demanding for mature (read: older) travelers.

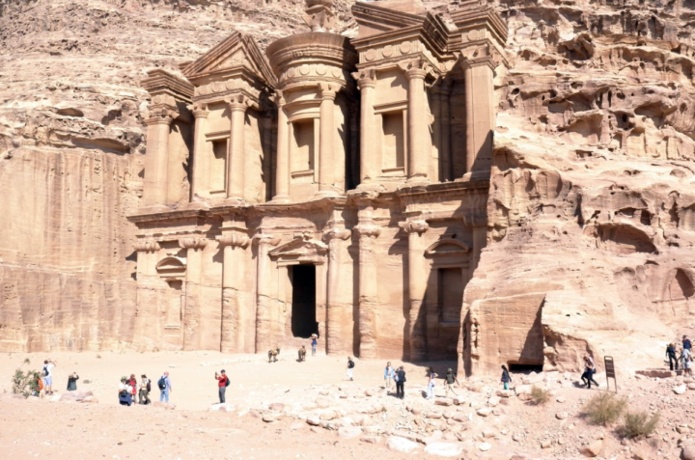

You would think that after this close call, I would stay on the flat and level. But following lunch at a pleasant restaurant next to the Qasr, we had the option of ascending to the second great site at Petra, the rock tomb of ad-Deir, “The Monastery” (another misnomer). This involved a climb of 750 vertical feet—800 steps up pebbly ground. Assured that there were no sharp drop offs (which turned out not to be entirely true), I had to press on, as did about half of our group. Here we are ascending:

And here, at last, with aching legs and panting lungs we reached the ad-Deir, certainly worth the climb.

Our group briefly gathered for a photo . . .

. . . when someone proposed a further scrambling ascent to high places above. From one of these, to the west, one could, like Moses at nearby Mt. Nebo, catch a glimpse in the distance of the Promised Land.

And below us, in the center and distance, the ad-Deir:

The descent, though faster, was no less punishing than the ascent. (As I write a day later my shins still hurt.) We emerged from the stairway beside the Qasr al-Bint. Here you can see the arch that stands before the Holy of Holies.

Walking out I couldn’t resist taking this snapshot of a fully modern donkey-taxi driver on his cell phone.

Having now walked about six miles and climbed up and down 800 steps. I accepted sharing a horse carriage ride back up the Siq with our physician, Dr. Maya Fehling. In retrospect, neither of us was sure that this fast bumpy ride across jagged Roman paving stones was any better than the three quarter mile hike.

With an hour’s rest, we all re-gathered for a brief lecture by Alan Mann on “Agriculture: The Beginnings of Civilization,” a talk well suited to the larger region around us and to the north where agrarian civilization began. Following this we departed in buses for Taybet, a restored traditional village and restaurant famed for its Jordanian cuisine (it was a favorite of King Hussein and his American wife, Princess Nor).

Greeted by traditionally dressed musicians . . .

. . . we dined on Jordanian mezze and roasted lamb. Returning to the hotel stuffed and exhausted, I didn’t even take out my Kindle, my usual bed-time accessory, but dropped into bed for 7 hours of dreamless sleep.

I’ll end this entry with a few words about Jordan. Overall, I was greatly impressed by the friendliness and modernity of the people. In many ways, Jordan is similar to Morocco: a modernizing Islamic constitutional monarchy, with established rights for women and minorities. Here, as in Morocco, is one of the many posters celebrating the royal (Hashemite) lineage.

Not depicted here, but on some other posters, is the youngest in line, eighteen-year old Hussein II, who, I was told, is now a student at Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service. This continues the educational practice of his father Abdullah II, who studied at Oxford and Georgetown. The culture as a whole seems slightly more Bedouin and less urban than Morocco’s, although that may reflect our distance from Amman. (The next morning, on the way to the airport in Aqaba, we stopped and took a two-hour detour by Landcruiser to the heart of the desert, where we had tea in a Bedouin tent.)

Throughout, I was impressed by our guides’ constant references to the nearness of Israel and the relative ease of movement back and forth. Sadly, they also reported on the enormous fiscal and other strains being imposed on Jordan today by the Syrian civil war and the over one million Syrian refugees now on Jordanian soil. Aid from the U.S., the U.N. and the Gulf States is helping, but this population is still a huge burden. The guides also lamented that the Syrian conflict and the turmoil in Egypt have reduced tourism to Petra and other sites by 80%. Preparing to depart for Morocco, I reflected on how important it is for our own country to support this progressive Islamic state.